When we think of Labor Day, what first comes to mind might be the end of summer barbecues or that final pool party, but Labor Day is also a reminder of the important role of labor in our society. The Department of Labor explains that Labor Day was established “when labor activists pushed for a federal holiday to recognize the many contributions workers have made to America’s strength, prosperity, and well-being.” It became an official holiday in 1894. Today, the efforts of laborers are just as crucial as they were back in 1894.

When you pick up a sumo orange from the local grocery store, the hands that originally picked that orange may not cross your mind. However, without that labor, we’d have more limited access to food. It’s easy to forget the role of labor in food production, but the industry heavily relies on employees for the high quantity and demand of food that we’ve grown accustomed to.

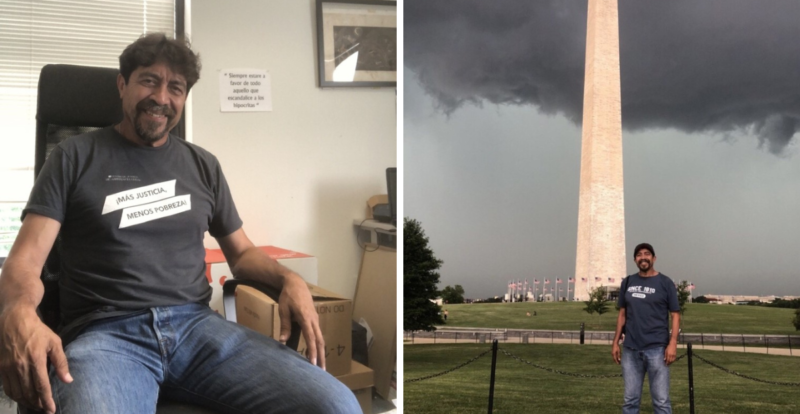

This year, in honor of Labor Day, I sat down with Arnoldo Borja, one of Food for Others’ Board Members, to discuss his experience working as a laborer in food production. Borja first immigrated to the United States from Mexico 29 years ago. In Mexico, he worked in agronomy, teaching and conducting research about food biology. When he first came to the US, he settled in Southern California. He began working on a farm harvesting oranges. In California, the work was very difficult physically. He started work at 4 AM and would work well into the evening. Borja explains that to pick oranges “you had to use a lot of strength to harvest from the top to the bottom.” He shared that “the containers were 100 + lbs, and you had to fill up containers of 10-11 bags.” Another element that made the work so difficult, Borja explained, was the extreme heat. Food Print writes that “few people feel [extreme heat] more acutely than farmworkers laboring for long hours under the sun. Dehydration and heat stroke are increasingly common. Even when workers avoid acute problems like heatstroke, they face longer-term issues: chronic dehydration can cause permanent kidney damage.”

After working in a few nonfood production roles, in construction and tobacco farming, Borja moved to Florida to harvest oranges for the season. Working in Florida, Borja’s new position required him to apply pesticides and drive a tractor. Borja explained that he was concerned by the use of the pesticide Roundup and that he asked his supervisor for protective equipment. He elaborated that “I started asking for special protection from the pesticides. I got fired because I was asking basic things.” Pesticide exposure is a primary concern among activists for better treatment of farm workers. Borja explained that “the effects of [Roundup] exposure aren’t immediately there, but it’s still harmful.” He was especially concerned that farmworkers were unprotected from it and would then wear their exposed clothing around their children.

Roundup, the pesticide Borja was concerned about, is one of the most widely used pesticides in farm work. It was created by the Monsanto company in 1974, but it first reached popularity in 1996 (New York Times). In the 90s, Monsanto began selling modified seeds that were resistant to Roundup. Since the seeds are resistant to Roundup, farmers could grow them and kill the weeds around them without accidentally hurting the crop. Studies are somewhat divided on the impact of glyphosate, the main ingredient in Roundup, but many argue that long-term exposure to glyphosate, the kind you experience from farming, is dangerous. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer identified glyphosate as a “probable carcinogen.” Web MD also explains that long-term exposure to glyphosate can irritate your skin, nose, and throat.

After being fired in Florida, Borja relocated to the Shenandoah Valley to work at a poultry plant. While working in the factory, he explains that “[he] saw that quality was not what they want[ed].” Borja saw firsthand the pressure for speed as he was assigned to work with a USDA representative to check poultry quality. Laborers at many meat packing plants face poor conditions. They have high rates of workplace injury and illness because “they labor in environments full of potentially life-threatening dangers” (Human Rights Watch). Human Rights Watch elaborates on these dangers; “Moving machine parts can cause traumatic injuries by crushing, amputating, burning, and slicing. The cumulative trauma of repeating the same, forceful motions, can cause severe and disabling injuries.” Like glyphosate for farmworkers, there are also chemicals, most often peracetic acid, utilized in the meatpacking process that are unregulated for long-term exposure to laborers. Peracetic acid is “abrasive to workers’ eyes, nose, and throat,” and they’re “essentially fumigated while they work” since its sprayed on the meat (Matt McConnel).

Borja’s work in Shenandoah Valley was his final experience working in food production. He currently works as a community organizer at the Legal Aid Justice Center. However, he still remembers how difficult food production work could be. In honor of Labor Day, Borja expressed that we should “appreciate how [our food] comes to the table.” He emphasized that “immigrant hands are everywhere” in the workforce and that “we need to trust each other and value the efforts of other people.” Just in time for Labor Day, Borja’s message is a great reminder of the value of labor and the importance of ethical treatment of employees.